To Jacinda Ardern, empathy is a political virtue

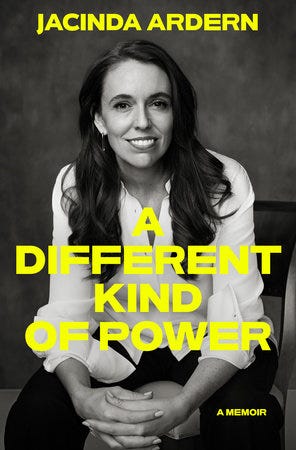

Publié le 14 juin 2025The former Prime Minister of New Zealand (2017-2023) has published her rich memoirs, “A Different Kind of Power”. It’s a fascinating book, firstly because it is so honest, without unpacking, secondly because it is all about politics through and through, and thirdly because it opens up perspectives in the current climate of geopolitical violence everywhere. I talked a lot about Ardern in my book “La démocratie féministe. Réinventer le pouvoir” (2020).

Ardern has been involved in politics since her high school days, and has made her mark in grassroots activism: canvassing, door-to-door, learning to speak in public – all experiences from which she quickly grasped all she could learn. Openness to others, ability to convince, hard work, curiosity and the desire to understand (explaining is not excusing, but enabling better action) have all forged her know-how and convictions. She then climbed the ladder one by one within the New Zealand Labour Party, becoming its leader at a time when it was at its lowest in the polls.

Favoring the arrival of a woman at the head of an organization in crisis has become a classic. What was not foreseen by her peers, however, was that in a few months, Ardern, destined simply to “save the furniture”, would manage to boost her party’s popularity spectacularly, win the general election and become head of government. Her mentors and role models were her two female predecessors in this position: Jenny Shipley and Helen Clark. This was a double turning point in her life, as she learned she was pregnant at the same time as being appointed Prime Minister, at the age of 37.

In her book, Ardern talks about the difficulty of resolving certain contradictions, but the satisfaction of taking on her battles. For example, she ended up breaking with the religious congregation she and her family had belonged to since childhood, the Mormons, because of their stance against LGBT rights. This forced her to distance herself from her grandmother, who nevertheless told her, just before she died, that she had always been proud of her.

The politics of kindness

Ardern is known for having made the 17 sustainable development goals the common thread running through her actions. She says that her taste for kindness and her interest in others (“being useful”) come from her parents (her father was a policeman, in particular), and that they have underpinned her actions and her way of governing throughout her political career. She rightly emphasizes that kindness does not mean weakness: “kindness gives hope, it transforms lives, it has extraordinary powers” and should invite new generations to renew politics. In terms of political agenda (a major plan for mental health as early as 2019 – well before our current governments -, a strong ecological commitment, a historic victory on the decriminalization of abortion, the promotion of “capitalism with a human face”, etc.) and leadership, kindness has been her common thread. Ardern explains that she has never considered aggressiveness to be a quality in politics, precisely because it is not a quality in life in general. On the contrary, kindness is a sign of strength, of holding society and the nation together, especially in times of crisis. “It is when the world is at its worst that we see the humanity of people,” she writes.

She experienced two major crises as she was Prime Minister: the Christchurch massacre in 2019, and Covid in 2020. The Australian terrorist who killed 51 people in two Christchurch mosques had written a 74-page paranoid manifesto detailing his hate project against religious pluralism and openness to others. In her hastily-written speech after the attack (which she says has scarred her forever), Ardern writes: « New Zealand is a home for all those, refugees and migrants, who are targeted by extreme violence. They are us”. She has always refused to publicly name the killer.

Trump: “would you call it terrorism?”

She also recounts the anecdote of a phone call with President Trump, who doubted the characterization of the assassin as a “terrorist” and asked her what the United States could do to help New Zealand at this difficult time. She replied that the best thing to do was to show compassion and love to all Muslim communities.

The law, passed unanimously (minus one vote) in ten days, which Ardern initiated after Christchurch, outlawed the possession of automatic military rifles and enabled the authorities to recover tens of thousands of such weapons from circulation within a few months. As with mental health, Ardern was a forerunner in calling for a “global response” to online terrorism.

Another key moment: the pandemic. The New Zealand government’s most important decision was to close the country’s borders and initiate a vast vaccination policy that gave the country one of the highest vaccination coverage rates on the planet, and saw life expectancy rise during this period, despite a very short (albeit very strict) containment period.

Jacinda Ardern, who does not like to be reduced to the embodiment of anti-Trumpism, is today, even more than five years ago, the counter-model of the current President of the United States and of all the virilist leaders: concern for others before concern for oneself, focus on the general interest, respect for one’s adversary, which in no way excludes firmness of decision and political authority, are no longer fashionable… for the time being. And it was because she no longer felt sufficiently able to serve her country’s interests that she chose to leave the political scene two years ago. “I mm happy because I know I have done my best” and “I have stayed the same”, she writes. Because politics is a serious issue, we need optimistic, combative books like this one.

Jacinda Ardern, “A Different Kind of Power”, First, 20.67 euros.